Holistic Psychotherapy & Healing

The Connecting Triangle

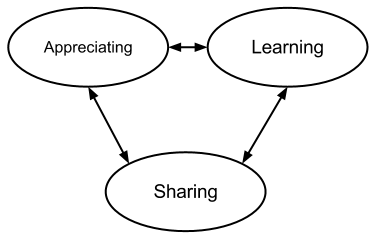

In my previous article, I talked about the Drama Triangle, in which people get caught up in the roles of victim, persecutor and rescuer – often without any conscious awareness. Luckily, there is an alternative. This is a very different dance, one that leads to connecting people in healthy, nurturing, and empowering ways. I call it the Connecting Triangle, and it looks like this figure:

In a dance with two people, one person may take the role of, say, Sharing – they talk about their thoughts, feelings and experiences, not to elicit help, pity or anger, but simply to share a portion of themselves. The other person can then find it easy to take the role of Learning – in which they are taking in and accepting new information with an open mind. Or, they might take the role of Appreciating – in which they affirm and validate what the first person is sharing. That in turn encourages the first person to share further, or to shift roles into Learning, prompting the second person now to share their thoughts, feelings and experiences.

The Connecting Triangle is available as a much healthier alternative for anyone who gets repeatedly entangled in the Drama Triangle. For example, if a person tends to habitually fall into the role of Victim, they may tend to cry out to others to save or rescue them (from who or what- ever is persecuting them). They can, by asking a certain frame-shifting question, make the transition into the role of Sharing.

Take the case of a woman who is in an emotionally abusive marriage. In the role of Victim, Sarah might have gone to her friend Jill to complain, “Pete drives me crazy. Nothing I do is good enough! He’s always telling me I’m a klutz…” But now suppose that Sarah asks herself the following frame-shifting question:

(Victim -> Sharing) “What do I know that is important to tell others?”

By asking herself this question, she might shift emphasis in her talk with her friend, and say instead, “I know I love Pete. I don’t like how he talks to me. I don’t know how to change him. I’m feeling pretty worn down and hurt.” Notice the prevalence of “I-statements,” popularized by Rogerian active listening techniques. This tends to happen spontaneously in Sharing – and very little in the role of Victim, where the focus is on identifying and blaming a Persecutor.

Similarly, a person who habitually falls into the role of Rescuer may be drawn into “fixing” a situation for a Victim. They can make the shift into Learning by asking the following frame-shifting question:

(Rescuer -> Learning) “What does this person already know that is important for me to understand?”

This question actually fosters two shifts. First, it stops the person from immediately jumping in to “fix” a chronic Victim-Persecutor dynamic between two other people, and instead helps them focus on learning more about the details of the other person’s experience. Second, it invites a person who is falling into a Victim role to consider the resources they already possess to solve the problem.

Sarah’s friend Jill, who earlier was being pulled in as a Rescuer, might, in asking this question, reflect back to Sarah, “I’d like to know how you have handled this up to now as well as you have. I also want to hear more about how you are feeling worn down. What do you think you need now?” These comments encourage and invite Sarah to take on the role of Sharing rather than of Victim.

Finally, a person who tends to habitually fall into the role of Persecutor is predisposed to start out by blaming or criticizing the other person. They may not do so in every area of their life, but perhaps only in one specific entangled relationship – and perhaps only intermittently, in between bouts of falling into Victim or Rescuer. In any case, they can make the shift into Appreciating by asking the following frame-shifting question:

(Persecutor -> Appreciating) “What qualities can I affirm about this person?”

Making the Shift

Take the case of a parent, Steve, who came in for therapy because his two older sons, ages 14 and 11, constantly fought with each other. On two or three occasions this escalated until Jordan, the younger and by far the smaller one, returned with a kitchen knife and threatened Max, the older son. Only then would the teasing and fighting stop between the two of them. The two boys were rapidly alternating between Victim and Persecutor. Upon interrupting the knife threat, for example, Steve was perplexed whether he needed to protect Jordan from Max's aggressive fighting, or Max from Jordan’s knife-wielding! In other words who was he supposed to rescue? He yelled at both of them, and lectured Jordan at length (throughout the following week) about “not crossing the line.”

In the family session where Steve described this event, he asked Max (the older son), “Why won’t you boys stop fighting?” Max looked away. Steve pressed him, “Well, answer me!” Max said, “No comment.” Steve persisted, “What do you mean! We are here to help you and your brother stop this fighting. Are you or are you not going to cooperate with this process?”

At this point, Steve, who came for treatment wanting to protect the children (Rescuer) was jumping over into berating both of them (Persecutor). He may also have been feeling helpless and frustrated (Victim) by their ongoing fighting. To help Steve enter the Connecting Triangle, I asked him to stop his line of questioning, and instead to pose the following question to the two children: “What does fighting do for you?” (Learning).

Jordan answered first: “It’s what brothers do.” Steve then began to challenge this, saying loudly and angrily, “What do you mean? Are brothers supposed to hit each other, to fight all the time, to threaten each other with knives?” I interrupted Steve and, looking at Jordan, said, “That’s a very interesting statement. What do you mean?” Notice that I ended on the same question that Steve began on, but the tone was completely different. It invited Jordan to continue Sharing rather than enter the Victim role, as Steve’s response would have done.

This time, Steve listened as Jordan explained more fully, “It’s like, we’re brothers, and brothers know everything about each other. They know each other’s weak points and stuff. And so it’s how we know that we’re really brothers, is by fighting each other, and hitting each other on our weak points. No one else but me knows the stuff that would get Max so riled up.” Max then added, “Yeah, and I know exactly what ticks off Jordan. He’s right, it’s like how we show that we love each other.”

I now prompted Steve, “This would be a good time to show them that you understand the good part in why they fight, even if you don’t like the fighting itself” (Appreciating). Steve said, “Well, you boys are saying you fight because that’s how you know you love each other. But aren’t there other ways to show your love?” Here, Steve automatically shifted from Appreciating into a Learning role. The boys both opened up more and talked about times they did feel cared for by the other one, or times they remembered doing special favors for each other (Sharing).

Over the next three weeks, Steve got more coaching in individual sessions about his tendency to berate the children when he felt frustrated or helpless by their negative behavior, and pointers on responding either by affirming a positive intent in the behavior, or by asking open-ended questions to elicit sharing. Within a month, the family was able to report a significant reduction in fights among the brothers (and no further knife-threats).

Final thoughts for therapists

The prime task of the therapist in helping clients resolve relationship entanglements is, above all, not to get entangled yourself. This is easier said than done. However, as with one’s clients, awareness opens the door to choice. If you (as a therapist) notice that you have a strong urge to jump in and “fix” something about the client or to “make it all better” for them, ask yourself the frame-shifting question to help you enter the role of Learning: “What does this person already know that is important for me to understand?”

As the client begins to share their own thoughts about the problem, the therapist can move between Learning and Appreciating as appropriate. “You’ve already figured out the things that don’t work for you in your marriage. And you wouldn’t be sticking around if you didn’t feel committed to making this marriage go well. What changes do you want to focus on making first?”

Finally, as an expert, it is part of your job to teach clients new perspectives on (sometimes) old problems. After all, if they could make these shifts on their own, they wouldn’t be coming to you to begin with. However, without trying to fix or rescue, an expert can nonetheless share information, for example, by saying, “There’s a diagram describing the kind of arguments you get into with your family that I think would be helpful to you. Would you like me to draw it for you, and we could see if it helps you make sense out of your situation?”

About Me

Ameet Ravital, PhD is a clinical psychologist with over 20 years of experience, in private practice in Philadelphia, PA.

Psychotherapy

I have a holistic approach to psychotherapy, which includes teaching mindfulness, self-acceptance, and conflict resolution skills.

Insurance & Fees

Here is a list of my current fees, as well as options for insurance reimbursement for psychotherapy consultations.

Copyright 2024, Ameet Ravital, PhD